My mother turned sixty last September, on the sixteenth. My parents were

both born on the sixteenth of their respective months but for some reason

growing up I was convinced that my mother was born on the fourteenth.

Every year I would get it wrong. Last September, on the fourteenth, two

days before my mother’s birthday, I asked her what her thoughts were

leading up to her sixtieth birthday, if she had any words of wisdom for her

daughter in her twenties.

“To be happy,” she said. Not so helpful, I thought. I asked her then if

she could give one piece of advice on life to me, or anyone, what would it

be?

“Life cannot be condensed to one word or sentence,” she said. Again,

not so helpful I thought.

My mother has never been afraid of ageing, unlike my father who

would spend money he didn’t really have on collagen serums and

expensive facewash, for men, of course. My mother wore the greying of

her blonde hair like highlights of a good life lived, and accredited the folds

in her skin to the range of emotions she has been able to experience,

nothing to be ashamed of.

“One thing that I have been thinking about,” my mother interrupted the

silence, “is that I will be turning the age that my mother was when she

died.”

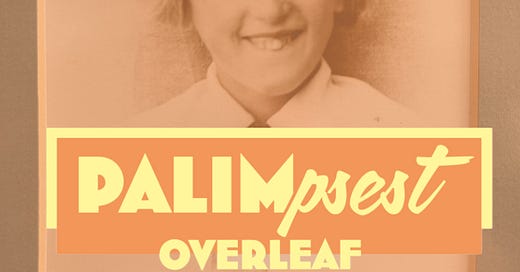

“Yeah,” I responded, and we sat in this for some time. I never met my

mother’s mother, which is why she has always been called my mother’s

mother and not Nan, or Gran, or Grandmother. I’ve seen pictures and have

always been told that I look like her, though she was still only my mother’s

mother. Always with that degree of separation in physicality and in

language.

“I always associated being sixty with being unwell and decrepit,” she

paused. “Old,” my mother added.

As a child, when my mother would talk about losing her mother in her

early twenties, I always thought that she was old. I never thought of my

mother as a confused child losing her support system, losing the answers to

all her questions, her back up, her leader, her best friend. To that younger

version of myself, my mother was an established adult losing her mother as

everyone will at some stage in their life.

And now my mother has turned sixty and she is neither unwell,

decrepit, or old. The version of sixty that my mother has created for me is

undeniably hardworking and passionate and unfalteringly stubborn to

complete everything that she sets out to complete, and to a standard higher

than anyone else. Not that completing something to a higher standard than

others is her intention, she just does. My mother’s version of sixty is

saying no to nothing, wearing those grey hairs and wrinkles with pride, and

yearning for grandchildren because caring for others is her passion.

My version of twenty-something would be devastated if I lost my

mother at sixty. It would be losing someone full of life who would have so

much more to give and experience, and I would not be an established adult

I would be merely faking it and hoping that I was doing it right, or at least

okay. And I would be losing the brightest and kindest support system I

could ask for; I would be losing my best friend.

It’s funny how perspectives of age change as one grows, and how ideas

of people are so different than who they actually are. I’ve never asked my

mother what it was like to navigate the transition into adulthood without

parents, or whether she felt like she had to fake it, or what her version of

being in her twenties was like and how different it was to mine. A big

difference is that mine is not parent-less, I guess.

Being twenty-something is being unsure, in love, loveless, happy,

sad, supported, unsupported, confused. And perhaps being sixty is no

different, but I won’t know until I am because just like my mother’s sixty

is different to her mother’s sixty, and my twenty-something is different to

my mother’s twenty-something, when I turn sixty, I will probably think of

my mother and how different my perception of her is to how I perceive

myself.

“I don’t think that you’re old,” I assured my mother, and she laughed

her hearty laugh which is one of the only expressions that still holds a firm

grip on the meaty Wirral accent. I’m not sure how a laugh can portray an

accent but hers does.

“That’s good,” she responded, “I don’t feel it.” We sat in the dulled

light of the living room over a glass of wine as is religiously done after

returning from a shift, two days before my mother’s sixtieth birthday.